The Life of Empress Theodora, the Nika Revolt of 532, and the Reconstruction of Hagia Sophia

- Kadir Küçükeren

- Aug 26, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Sep 3, 2025

The Origins of Theodora and Her Rise to the Throne

Theodora was born around the year 500. Her father was a bear keeper in the Green faction at the Hippodrome of Constantinople, while her mother was a dancer and actress. Theodora's family were not noble. After she lost her father at a young age, her mother remarried, but the family fell on hard times. She took her three daughters — Theodora, Komito and Anastasia — to the Hippodrome to ask spectators for help. When the Greens refused to offer her mother a job, the Blues took the family in and hired her stepfather. This meant that Theodora grew up in a Greek-speaking environment in Constantinople during her childhood.

According to sources from the period, Theodora began her career performing on stage as a young theatre actress and also worked as a sex worker. The most detailed account of this period of her life can be found in the work Secret History, written by Procopius, the historian of Emperor Justinian. Procopius claims that Theodora worked in a brothel from a young age, performed obscene shows on stage and even fed grain sprinkled on her naked body to geese while re-enacting the myth of Leda and the Swan. However, modern historians point out that Procopius' portrayal may be exaggerated and biased; indeed, his purpose in Secret History was to discredit the emperor and his wife, so the reliability of his narrative is questionable. Nevertheless, this source shows that Theodora came from a modest and even scandalous background.

A turning point in Theodora's life was the relationships she formed with statesmen while pursuing her career in the theatre. Around the age of 16, it is known that she travelled to North Africa with her lover (or patron), Hecebolus — a Syrian-born official — and lived in the Pentapolis region of Libya for a time. After the relationship ended badly, Theodora stayed in Alexandria for a while on her way back from Africa. According to legend, she met the Miaphysite patriarch Timotheos there and became interested in the Christian sect, but there is no definitive evidence to support this claim. After Alexandria, she visited Antioch and befriended a dancer named Macedonia. In 522, she returned to Constantinople, leaving her old life behind to take up a modest occupation such as spinning wool in circles close to the palace.

Thanks to her beauty, intelligence and wit, Theodora caught the attention of General Justinianus, who was the heir apparent at the time. He became passionately attached to her and wanted to marry her. However, it was illegal for a member of the imperial family, especially the future emperor, to marry an actress. A law dating back to the reign of Emperor Constantine prohibited senators and high-ranking state officials from marrying actresses, who were considered to have a low social status. Justinian's aunt, Empress Euphemia, wife of Emperor Justin I, also strongly opposed the marriage. Nevertheless, Justinian was determined, and after Euphemia's death in 524, he persuaded his uncle, Emperor Justin I, to change the law. The new law permitted women who had previously worked as actresses to marry someone from the upper class with the emperor's consent. After the law was changed, Justinian married Theodora (probably in 525). Theodora had a daughter from a previous relationship, the father of whom is unknown. Thanks to the same law, this daughter, who was born after her marriage to Justinian, was also given the opportunity to marry into the nobility. When Emperor Justin I abdicated in 527, Justinian became emperor and Theodora was officially proclaimed empress with the title 'Augusta' on 1 April 527.

Historians have assessed Theodora's personality and influence in different ways. In his work 'Wars', which is considered an official history, Procopius praises Theodora as a brave and loyal wife during the Nika riots. However, in his 'Secret History', he portrays her as a ruthless, ambitious and lustful 'tyrant'. In particular, Procopius portrays Theodora as cooler-headed and more courageous than her husband during the Nika Revolt in order to make Justinian appear cowardly, even adapting sayings attributed to ancient despots to her. Other contemporary historians, such as Malalas and Evagrius, have portrayed Theodora's actions in a more positive or neutral light. In modern historiography, Theodora is widely regarded as one of the most powerful and influential women in Byzantium. Her role as a saviour during the Nika Revolt and her legal reforms concerning women's rights (such as regulations expanding women's rights to divorce and property ownership) are particularly emphasised. Despite coming from a low social class, Theodora managed to rise to the top of the empire, share power effectively, and leave a lasting mark on politics and society as a historical figure.

Theodora and the Nika Revolt of 532

Theodora's political and personal courage was most clearly demonstrated during the Nika Revolt of 532. Considered the most serious crisis of Emperor Justinian's reign, this uprising initially erupted when a Hippodrome event spiralled out of control, but its roots lay in deep socio-political tensions. In Byzantium, two major factions supporting the Hippodrome races — the Blues and the Greens — operated as sports fan clubs and socio-political groups in the 6th century. At the Hippodrome of Constantinople, which could hold 100,000 people, the emperor could make direct contact with the public. During the races, the crowd would shout cheers and slogans to convey their demands to the emperor, expressing their dissatisfaction or support. Although initially just team colours, the Blues and Greens eventually began to influence imperial politics. Emperors generally tried to secure popular support by aligning themselves with one of these factions. For example, during the reign of Anastasius, the emperor distanced himself from the Blues and Greens and supported the Red faction, leaving him facing the combined opposition of the two major factions. Justin I and Justinian supported the Blues; Justinian, in particular, turned a blind eye to Blue hooligans before ascending the throne in order to secure his succession. Once on the throne, however, he began to take tougher measures against the factions to maintain balance, creating discontent in both groups, including his former supporters, the Blues.

The spark that ignited the Nika Revolt began on 10 January 532, when some members of the two rival factions were sentenced to death. Those who had committed murder during the previous race riots were arrested, including some Blue and Green supporters, and the city prefect, Eudaimon, decided to have them hanged. However, while the executions were taking place, the gallows collapsed, miraculously saving the lives of one Blue and one Green supporter. These two survivors took refuge in a monastery. Some people interpreted this event as a divine sign, prompting both factions to appeal to the emperor for the prisoners to be pardoned. At the Great Hippodrome Race on 13 January 532, the Blues and Greens acted together in an unusual manner to reiterate their demand for the prisoners' pardon. However, Emperor Justinian remained silent and refused to grant clemency. In response, the Blues and Greens, who had been rivals in the stands for years, rose up together in shared anger, shouting 'Nika!' (Greek for 'Win!' or 'We will conquer!'). This unity was a rare occurrence in the history of Byzantine insurrections and signalled a reaction to Justinian's inconsistent factional policies. Historian Geoffrey Greatrex emphasises that the emperor's indecisive and ambivalent attitude during this period triggered the rebellion. Some researchers (e.g. Mischa Meier) even suggest that Justinian deliberately provoked the rebellion to expose dissident senators or make room for his construction projects.

In the early days of the uprising, public anger spiralled out of control and the centre of Constantinople turned into a battlefield. Spilling out of the Hippodrome, rebels spread into the streets, chanting 'Nika!' and setting government buildings ablaze. The rebels' first target was the praetorium of Eudaimon, the hated city governor – this building was burned down. Then important buildings, including the Hagia Sophia Church, were set alight; the frenzied crowd started fires everywhere. According to contemporary sources, almost half of the city was reduced to ashes in the fires. For example, the 7th-century Paschal Chronicle states: 'A very large part of the city was burned to ashes by an unprecedentedly large fire, from sea to sea; the Great Church (Hagia Sophia), Hagia Irene, the Samson Hospital, Augusteion Square and the Chalkê Gate of the palace were completely burned down.' During the five-day uprising, public buildings, baths, churches, shops and even parts of the imperial palace were destroyed by the rebels. Justinian was helpless in the face of the inadequacy of the guard units, which were unable to maintain order in the capital. The rebels found support not only in the streets, but also among the empire's ruling elite. Some senators, dissatisfied with heavy taxes and Justinian's authoritarian reforms, took advantage of the uprising to incite unrest behind the scenes. First, the rebels demanded that the emperor dismiss three high-ranking state officials: Eudaimon, the city prefect whom they hated; John the Cappadocian, the emperor's tax collector; and Tribonian, his legal advisor. Justinian immediately accepted these demands in the hope of quelling the uprising, removing the officials from their posts. However, these concessions were not enough to calm the crowd.

In its second phase, the uprising shifted to directly targeting the throne. As clashes intensified between 15 and 17 January 532, some dissident senators encouraged the rebels to proclaim a new emperor. Two of the most prominent figures were Hypatius and Pompeius, who were the nephews of Justinian's late predecessor, Anastasius. Initially under Justinian's protection in the palace, on the morning of Sunday 18 January, the emperor expelled both Anastasius's nephews (perhaps fearing for his own safety). As soon as they were outside, the rebellious crowd captured Hypatius and proclaimed him emperor. Hypatius initially hesitated, but was forced to lead the rebels. He donned the imperial cloak and took his place in the imperial box at the Hippodrome. The situation had now become a matter of life and death for Justinian. Should he flee the capital to save his life, or fight to the death to defend his throne? At this critical moment, he held an emergency meeting with his advisers. According to the historian Procopius, the emperor was overcome with fear and was considering preparing the fleet to escape by sea. Most of the state officials were also concerned for their own lives and urged the emperor to retreat. The only person to speak during the meeting was Empress Theodora.

In that famous speech, Theodora demonstrated her legendary resolve. Vigorously rejecting plans for her escape, she declared that the noblest death for a ruler was to die fighting. According to Procopius's records, Theodora said, “It is better to die as emperor than to live in exile or as a fugitive. The royal purple is the noblest shroud.” (Here, “purple” symbolizes the imperial purple robe, representing sovereignty.) Theodora’s words — “Purple is the best shroud!” — shook the court, instilling a mixture of courage and shame.. Thanks to this historic speech, Justinian and his ministers were galvanised. The emperor dismissed the idea of fleeing completely and turned his attention to planning a counterattack. Theodora's stance may have changed the fate of the Byzantine Empire, because if the emperor had fled, the success of the rebellion and the overthrow of the dynasty would have been almost inevitable.

Justinianus wasted no time in mobilising his loyal commanders to suppress the rebellion. A plan was devised by General Belisarius, General Mundus and the palace eunuch Narses. Narses took gold to the Hippodrome in an attempt to bribe some of the leaders and members of the Blue faction to join his side [65][66]. Meanwhile, Belisarius and Mundus gathered the imperial military units and surrounded the Hippodrome on two sides. On the night of 18–19 January, imperial forces suddenly raided the Hippodrome. Seeing that the corridor leading to the imperial box was held by rebels, Belisarius entered through a different gate and attacked the tens of thousands of rebels gathered in the arena [67][68]. Meanwhile, General Mundus was slaughtering the rebels remaining outside. That bloody night, amid little light and a chaotic crowd, a massacre took place – one of the greatest in Istanbul's history. Procopius, who witnessed the events alongside Belisarius, provides a detailed account: The imperial soldiers indiscriminately slaughtered the crowd in the Hippodrome; those who tried to escape were crushed in the stampede. According to Procopius, 'more than 30,000 people lost their lives' that day [69]. Other sources give an even higher death toll of around 35,000. For example, Theophanes and the Paschal Chronicle report that around 35,000 rebels and civilians were killed that day. Some later exaggerated accounts even claim that the death toll reached 40,000. While the exact number is unknown, the Nika Revolt is remembered as one of the bloodiest urban uprisings in history.

By morning, the bodies of those killed in the uprising had been piled up in the Hippodrome, and the revolt had been crushed. Emperor Justinian immediately took measures to exact revenge and restore order. Hypatius and his brother Pompeius, whom the rebels had declared puppet emperors, were captured and brought before Justinian. Despite their claims of innocence, Justinian had them executed immediately (according to some sources, Theodora insisted on this ruthless course of action). Senators who had participated in or supported the uprising behind the scenes were punished: some were exiled, while others had their titles and property confiscated. However, a few years later, the emperor adopted a more forgiving attitude in order to achieve political harmony. Some of those who had been exiled, such as the Minister of Finance John of Cappadocia, were reinstated to their positions. The children of those whose property had been confiscated were given compensation and new titles. In this way, Justinian partially repaired the divisions created by the rebellion. Although the emperor's authority was consolidated after the uprising, factional violence did not end completely in Byzantine society. Indeed, in the final year of Justinian's life (565), a new state of emergency was required to disperse the Blue and Green factions when the Hippodrome riots again became deadly.

The Nika Revolt had a profound impact on Byzantine history, both in terms of its causes and consequences. The uprising was triggered by the people's pent-up anger over heavy taxes and unjust practices, as well as by the emperor's uncompromising authoritarian reforms and conflicts of interest within the palace. While the people's anger during the uprising may have been justified, the consequences were disastrous: within a week, the capital had been reduced to ruins and tens of thousands of people had lost their lives. From Justinian's perspective, the Nika Revolt was a valuable lesson: it showed the emperor how vital popular support was while intimidating his enemies and allowing him to consolidate his absolute power for the remainder of his reign. Theodora's role reached legendary status: her leadership during a time of fear led the people to hail her as 'the actual saviour of the state'. Procopius expresses his admiration for her courage in passages implying that 'Theodora saved the empire more than her husband did'. Even in subsequent centuries, Theodora's words during the Nika Revolt remained on the lips of historians and writers.

The reconstruction of Hagia Sophia after the Nika uprising (532–537)

Immediately after suppressing the Nika Revolt, Justinian began imposing punishments while also undertaking urban development projects in the city. The extensive destruction caused by the uprising presented him with an opportunity for large-scale reconstruction. Rebuilding the Hagia Sophia church, which had been reduced to ashes in the fire, in an even more magnificent form than before, became one of the emperor's priorities. Construction of the Hagia Sophia began in February 532, just 39 days after the uprising had been quelled. To lead this massive project, Justinian brought the most famous architects and engineers of the time: Anthemius, a geometer from Tralles (modern-day Aydın), and Isidorus, a physicist from Miletus (modern-day Balat), were appointed as chief architects. The project was so large that 100 architects, each with 100 workers under their command, were employed as site managers; thus, with approximately 10,000 workers, construction progressed as if it were a mobilisation. The emperor sent decrees to governors and vassal kings throughout the empire ordering them to send the most valuable architectural materials from their regions to Istanbul for the construction of this great temple. Consequently, columns, marble and capitals dismantled from various ancient temples and buildings were transported to the capital.

Some of the materials used were:

⦁ Marble and columns: Bright white marble slabs were brought in from Marmara Island; green somaki marble from Euboea Island; pink veined marble from the vicinity of Afyon (Synada); and yellow-toned marble from North Africa. Green-veined columns salvaged from the ancient Temple of Artemis in Ephesus were brought in, as were eight large red porphyry columns dismantled from Heliopolis in Egypt and used under the half-domes.

⦁ Stone and bricks: The main supporting pillars (column bases) were made of solid limestone. Brick was the preferred material for the wall bodies, especially for the dome construction. This was because, unlike wood, brick was not combustible and imposed a lighter load when covering large spans. To further lighten the dome, very light bricks made from volcanic soil on the island of Rhodes were used. The governor of Rhodes had these bricks cast in special moulds and shipped to Istanbul quickly.

⦁ Mortar and other techniques: Specially formulated mortars (probably lime mortar with saltpetre) were used to bind the brick arches. The arch and vault techniques developed by the Romans to span wide openings were applied on a scale never before seen in a church at Hagia Sophia. The emperor also brought the finest column capitals and decorative elements from ancient quarries around Bithynia, adding aesthetic richness to the structure.

From an architectural perspective, the new construction of Hagia Sophia was revolutionary. While previous basilica-style churches had flat wooden roofs or small domes, Hagia Sophia was the first fully domed basilica. A massive main dome, measuring 32 metres in diameter, covered the central space and was supported by half-domes on four sides. This dome was supported by four main pillars (columns) and the arches above them, with pendentives connecting these arches at the corners. The pendentive technique is an engineering solution that enables a round dome to be placed on top of a square-plan space. Hagia Sophia was a breakthrough in architectural history as it was the first structure to implement a large dome with full pendentives, and it is said to have 'changed the course of architecture'. A continuous row of windows opening onto the base of the dome filled the enormous structure with light, creating the impression that the dome was suspended from the sky. Indeed, the Byzantine historian Procopius describes the dome of Hagia Sophia admiringly as 'hanging from the sky as if suspended by a chain'. As the load carried by the dome was transferred to the side arches and then to the foundation via the pendentives, it was possible to span unprecedentedly wide openings without interior columns. Consequently, when Hagia Sophia opened, it became the place of worship with the largest interior volume in the world.

Construction progressed at an astonishing pace, taking approximately five years and ten months to complete. On 27 December 537, Emperor Justinian personally presided over the opening ceremony, consecrating Hagia Sophia for worship. According to legend, moved by the size and splendour of the temple, the emperor declared the magnificence of his own work, saying: 'O Solomon, I have surpassed you!', in reference to Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem. On the opening day, the people were mesmerised by the beauty of Hagia Sophia. The interior was adorned with gold mosaics, and the light filtering through the forty surrounding windows shone on them, creating a sublime atmosphere. Unfortunately, just 20 years later, Hagia Sophia's massive dome, which gave the impression of 'floating in the air', faced its first serious test when it cracked and collapsed on the eastern side during the earthquake of 558. Justinian immediately commissioned Isidoros' nephew, Young Isidoros, to rebuild the dome. This time, the dome was raised even higher, a low drum supported by buttresses was added, and the number of windows was increased to forty. Once the repairs were completed in 562, Hagia Sophia acquired its current form of dome.

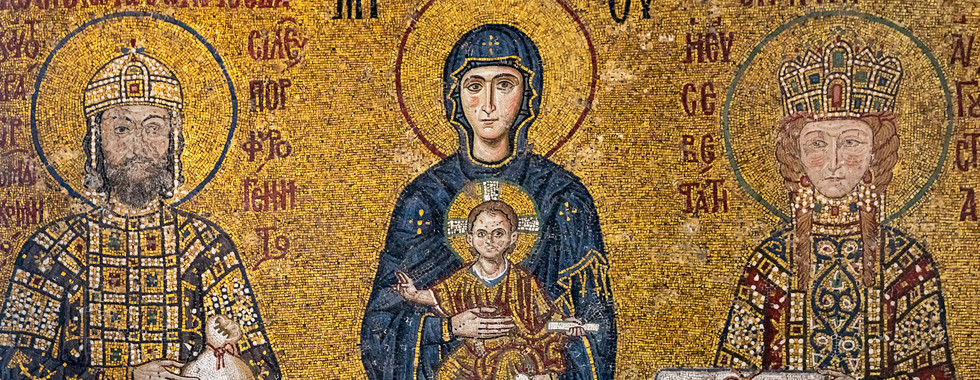

The Hagia Sophia is widely regarded as the pinnacle of Byzantine architecture. Its significance lies not only in its size, making it the largest temple of its time, but also in the architectural innovations it introduced. By combining a central plan with a basilica plan, the Hagia Sophia became known as the 'jewel of the Eastern Roman Empire'. Indeed, from its completion in 537 until 1520, it remained the world's largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years. However, it was surpassed in size by the Cathedral of Seville in Spain when it was built in 1520. The Hagia Sophia served as a model for countless structures built in the following centuries: Churches in the East in particular adopted its domed basilica layout, such as the Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki and the Hagia Irene in Istanbul. Furthermore, during the Ottoman period, Turkish architects led by Mimar Sinan carefully studied Hagia Sophia in an attempt to surpass it. Traces of inspiration from Hagia Sophia are clearly visible in works such as the Süleymaniye Mosque, the Şehzade Mosque and the Sultanahmet Mosque. Hagia Sophia is considered by architectural historians to be a 'unique monument' and 'a symbol of an era in itself'. This structure embodies the grandeur of the Byzantine Empire and is the most enduring witness to the legacy of the reign of Justinian and Theodora.

Bibliography

Procopius, 'Wars' and 'Secret History'; John Malalas, 'Chronicle'; Paschalis Chronicle; Theophanes, 'Chronicle'; J. B. Bury, 'History of the Later Roman Empire'; Geoffrey Greatrex, 'The Nika Riot: A Reappraisal'; A. Cameron, Procopius and the Sixth Century; and Çiğdem Dürüşken, Byzantine History.

This is a view of the interior of Hagia Sophia from below, showing the main dome and half-domes. The large central dome is supported by four pendentives and is constantly illuminated from within by the windows at its base. Depictions of six-winged angels (seraphim) adorn the dome's pendentives.

Hi, just have questions, what's the text right in the middle say?

It was a truly enjoyable and insightful read, thank you so much 👍☺️